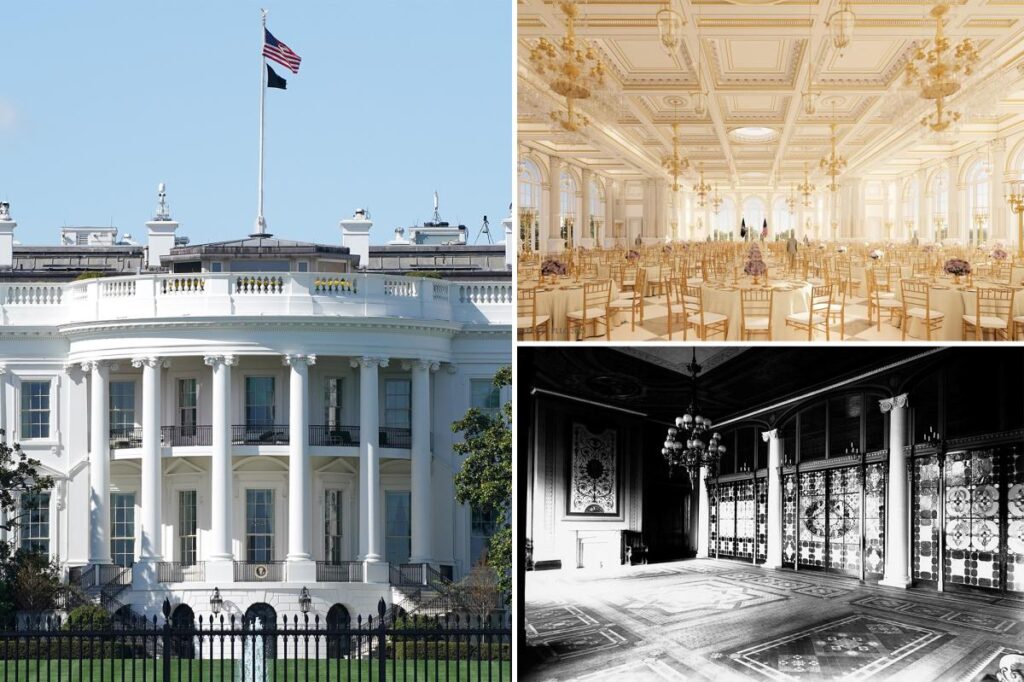

While future guests of the White House will be having a ball in its forthcoming ballroom, for which demolition began on Monday, the massive renovation isn’t the first of its scale at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

Since its debut in 1800, and reconstruction in 1817, the presidential residence has seen a number of major facelifts.

President Trump’s, of course, is the most recent — and will cost a grand $250 million.

The ballroom will now have capacity for some 900 people, a 40% increase from the plans that were announced in July. Back then, the White House said it would fit 650 people at 90,000 square feet, with a cost of $200 million.

“We’re gonna have a phenomenal ballroom, this is gonna be one of the best anywhere in the world. There won’t be anything like it, actually,” Trump told project donors last week. He had previously said that a ballroom of this scale is necessary for hosting leaders and foreign dignitaries at the White House; using tents on the South Lawn, he also said, is inadequate.

“And it’s four sides of glass, beautiful glass, but totally appropriate in color and in window shape, and everything else with the White House.”

Since the summer, project renderings have shown floor-to-ceiling arched windows that complement chandeliers draped from coffered ceilings. They also show the ballroom’s exterior will match the White House’s overall aesthetic. It’s all inspired by Trump’s own ballroom at Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach.

Monday’s demolition began on the East Wing, which Trump is lengthening for the ballroom. As it stands, the East Room is the largest event space inside the White House, with seats for about 200, though more if they’re packed like sardines.

But there’s far more history beyond the scope of this current work. Read on for some of the biggest undertakings that have happened in the property’s 225-year history.

1817

Today’s White House reigns mighty, and has long been a popular stop for photos among tourists visiting DC, but it’s not the original.

In 1814, during the War of 1812, British troops set fire to the White House for the American attack on the city of York, Canada — now part of Toronto — in 1813. Now known as the Burning of Washington, the attack also targeted other US government buildings. But that on the White House displaced President James Madison and his First Lady Dolley — who had already fled into hiding — for the remainder of the term, according to the History Channel.

An Irish-born architect named James Hoban oversaw the reconstruction, which reached completion in 1817. And he was quite the expert as it was. Hoban submitted President George Washington’s favorite plan for the original presidential residence in a design competition. Work on that property kicked off in 1792 and wrapped in 1800. During the reconstruction following the blaze, Hoban worked alongside an architect named Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

Hoban is also credited for adding the South Portico in 1824 and the North Portico in 1829.

1902

President Theodore Roosevelt tapped the architect Charles F. McKim — of New York’s famed Gilded Age architectural firm McKim, Mead & White — to usher in a new era for the White House, as DC had begun to fill with dignitaries from around the world for the very first time.

At this time, the goal was to expand the White House’s footprint, according to the White House Historical Association, as the property itself was the landmark of official society in the United States.

Most notably, this work brought about the famed West Wing, which today houses the Oval Office. But at the time of this expansion, the Temporary Executive Office, as it was then known, was an executive office building for the president’s staff, though not Roosevelt himself, who had a “workroom.”

The Oval Office arrived in 1909 when the size of the West Wing was doubled. President William Howard Taft was its first occupant.

McKim and his team also devoted special attention to the state floor — a gala area. An old staircase was removed, its own space then blended into a dining room, which yielded an event space that could hold more than 100 visitors. First Lady Edith Roosevelt became very involved in its interior design, with the historical association noting that all fabrics and furniture had to pass her approval. One of those touches she allowed was the cobalt blue silk that dressed its walls.

If it sounds expensive, that’s because it was. The work cost $65,000 — more than $2.2 million today.

1942

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration saw the monumental addition of the White House’s East Wing for additional office space — and staff members to fill it.

That came in tandem with a growing federal government during World War II — and the construction was regarded as controversial during wartime, according to the historical association.

However, there was a greater mission at hand. The East Wing was added to conceal an underground bunker now known as the Presidential Emergency Operations Center, according to Architectural Digest.

Over time, the East Wing began serving as office space for the First Lady and her staffers.

1948 to 1952

Today’s work on the White House is nothing to sniff at, but the White House’s most significant renovation came during President Harry Truman’s administration.

Engineers discovered the White House was in danger of collapsing due to weakened wood beams, and outdated plumbing and electrical systems, according to its historical society.

“Some said the White House was standing only from the force of habit,” its website says.

For a cost of $5.7 million — $77.91 million today when adjusted for inflation — a total interior reconstruction ensued. Only the outer walls were preserved, while everything inside was rebuilt with the far more modern materials of concrete and steel.

The work wasn’t without its critics, especially from media outlets that questioned the construction’s cost in the post-war economic recovery. In reality, no one was really pleased. Staunch preservationists objected to the loss of the original interiors. Truman was a Democrat and Republicans accused him of mismanaging funds — and some said less extensive repairs would have done the job.

Despite it all, the scope of this work has allowed the White House’s structural integrity to remain mighty to this day.